The theme for this year’s International Women’s Day is to #BeBoldForChange with the goal of continuing to create a more inclusive, gender equal world. In honor of yesterday’s International Women’s Day, this post responds to one call of action to: “be bold and forge women’s advancement”.

Despite widespread initiatives aimed at diversity and inclusion, mentorship and guidance, and full-on support of helping women achieve gender parity in leadership roles, many organizations continue to fall short. The reasons for this are complex. However, part of it may be due to stereotypical beliefs regarding how leaders should behave.

Do you know a High Potential when you see one?

Decades of social science research suggest that, particularly when we’re cognitively taxed, we tend to revert to assumptions and generalizations to help us make sense of our environment. Generalizations on their own are innocuous; however, when they guide our expectations, behaviors, and decisions they become problematic.

For example, in male-dominated organizations, we tend to see very few women in leadership roles. Without focused energy and efforts to disrupt it, this becomes a cycle. When you’ve always worked for and looked up to male leaders, that prototype begins to shape your expectations regarding leadership in general which could result in the selection of more male leaders, while female leaders are inadvertently overlooked.

Combine this with a world that suffers from information overwhelm, and it’s quite possible that when it comes to identifying and selecting High Potentials, we’re not paying attention to something we should.

In a recent publication by Hogan, they suggest that “performance reviews and supervisor nominations tend to be good at identifying the people in organizations who ‘look’ like leaders,” – that is, the typical ways we assess performance and potential are, in and of themselves, fraught with bias. This is not a novel argument. However, combine this with our increasingly overwhelming surroundings, and it seems likely that we’re more prone than ever to falling back on generalizations when making decisions about who is a HiPo.

Defining High Potential Leaders

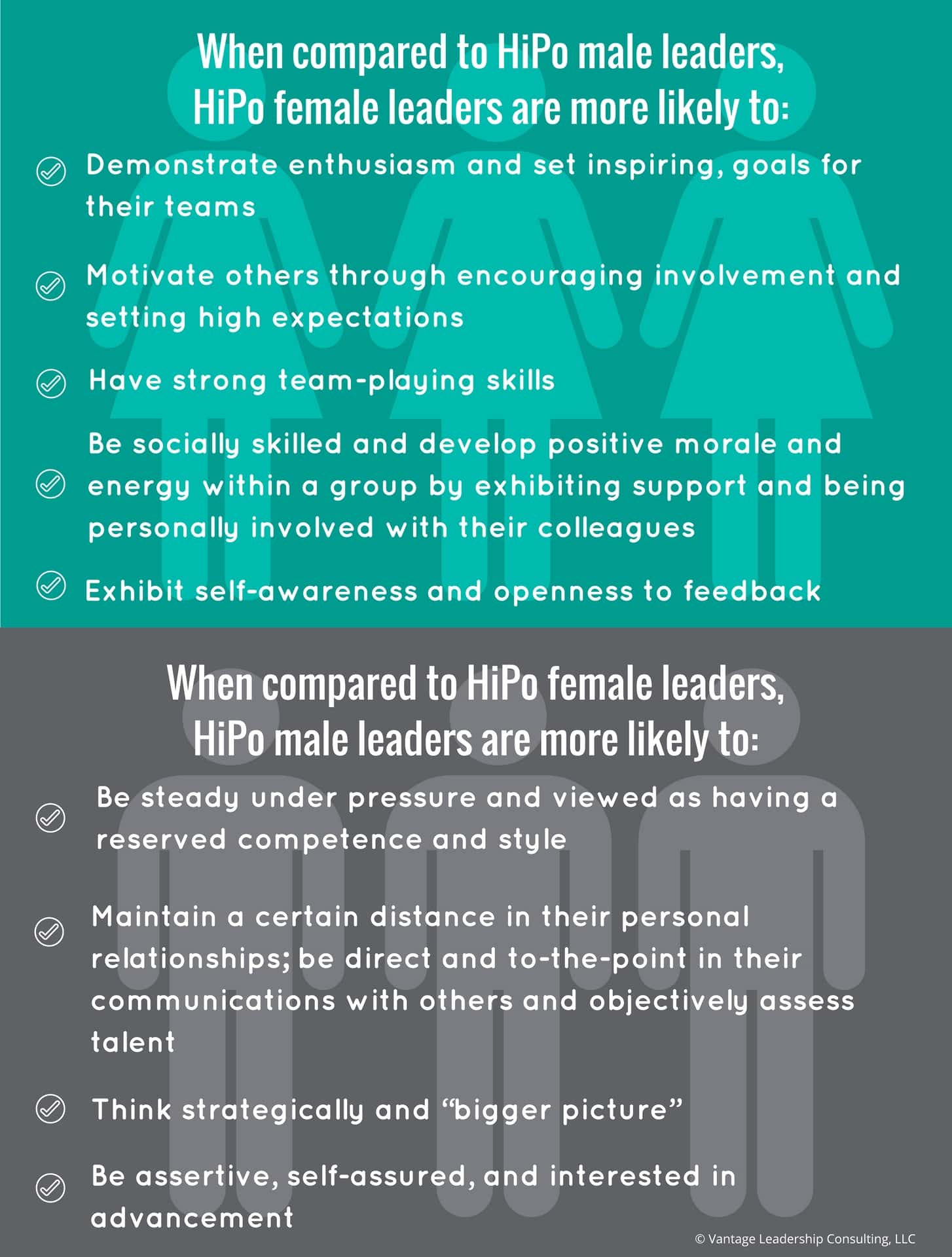

With this in mind, we recently presented research on what it takes to be considered a High Potential leader at the Society of Consulting Psychology Conference in Seattle. In particular, our research focused on whether there are differences in leadership style and behaviors exhibited by male and female high potentials.

Our Method

We used a database of 700+ candidates who were assessed for managerial positions; about a quarter of the sample was female, and, on average, candidates were 44 years old. As part of their assessment, they all completed self-report measures of leadership behavior and personality characteristics. We also collected on-the-job performance and potential data for all candidates from their current boss. To be considered a HiPo in our research, candidates had to be rated in the top 20% of the sample in terms of their advancement potential.

Here’s what we found.

You might recognize that the profile of a high potential female leader that emerged from our data maps onto a transformational, participative leadership style. This leadership style is characterized by creating a vision and building commitment and followership by influencing through emotional appeals and charisma. It’s a style that tends to be highly regarded and is quite impactful in challenging times (like, for example, our current business landscape). So it’s not surprising that those who exhibit this style are viewed as high potentials.

The leadership style depicted for HiPo male leaders on the other hand, maps onto a style characterized by being assertive, confident, and more focused on tasks and results than relationship. This is more aligned with traditional assumptions regarding what effective leadership is. In fact, when we see this approach, we might say that this person is “leader-like.” As mentioned above, our traditional performance measures identify those who ‘look like’ leaders (which would often be High Potential male leaders). This is the “think manager, think male” paradigm in action.

What is the impact of these differences?

Given that we all have assumptions regarding what effective leadership looks like, we could very well be overlooking HiPo leaders (female and otherwise) who enact a different, yet highly effective, set of behaviors and skills.

This research serves as a reminder that, to continue creating a more inclusive working world, we need to take time to reflect and remind ourselves not to fall back on outdated assumptions and instead, recognize that effective, high potential leaders come in many shapes, sizes, and genders.

Moreover, this research further corroborates a theory that we, at Vantage, have always subscribed to: leadership is not one size fits all. Long gone are theories that focus on one specific set of behaviors to define effective leadership. Rather, we must consider context, setting, and organizational needs when selecting and promoting individuals to leadership roles. And, having diversity in leadership style and approach only improves an organization’s capacity to deliver value and maintain a competitive advantage.

And to stick with the #BeBoldForChange theme, our call to action is this: Take an uninterrupted moment to reflect on how High Potentials are defined in your organization. Are there individuals being overlooked solely because they may not fit the standard mold?

Curious about your own implicit gender bias? Harvard has several bias tests available to you, including ones that look and gender and career and gender and leadership. (Responses to these tests are used by Project Implicit for research purposes.)